One of my favorite contributors to the Berkeley Bussei is Hiroshi Kashiwagi. I don’t talk about him nearly enough in The Book, but only because I don’t talk about anyone nearly enough. (Turned out to be not that kind of book, but that’s a different story.) But lucky for us, I can talk about him more here.

Kashiwagi was born in Sacramento in 1922. After the war, after illegal incarceration, after earning degrees from UCLA and UC Berkeley, he became a playwright and actor. Later in his life he wrote a memoir, Swimming in the American, which is, hands down, the best title for a memoir ever. (That’s hyperbole, of course, but also a hill I’m willing to die on.) In it, he talks about his experiences growing up in Central Valley farming towns, the tensions between white people and the Japanese community, and his coming to terms with his American identity. Not insignificantly, he dedicated his memoir to Wayne Collins, a civil rights attorney who helped Japanese Americans who had renounced their citizenship in the camps to regain their citizenship and, to paraphrase Kashiwagi, restore his faith in America. (These are some of the reasons Swimming in the American is the best title ever.)

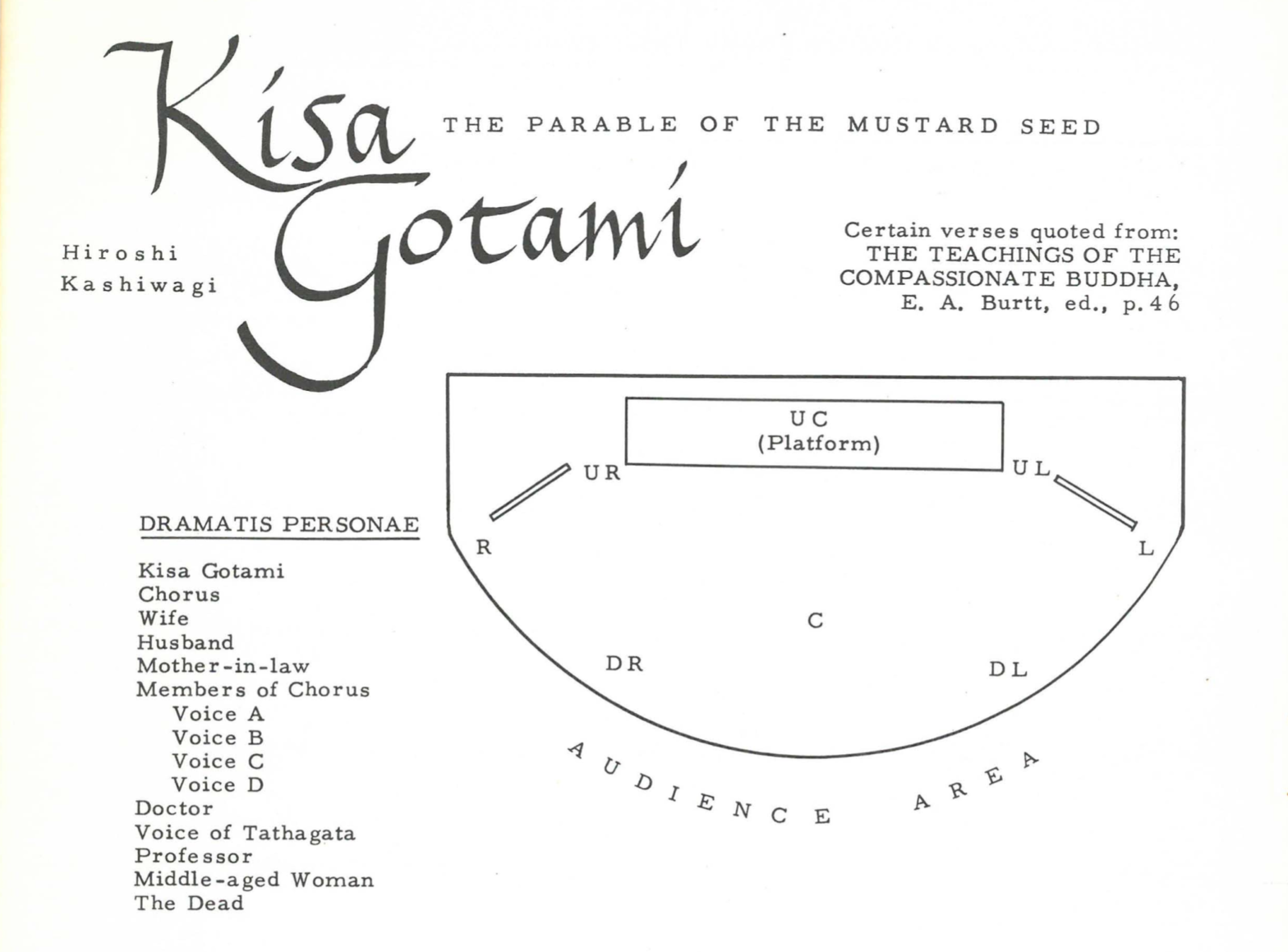

In sitting down to write this blog post, I did some quick internet searches to add all the hyperlinks, like you do. And I found Kashiwagi’s Wikipedia page. It lists the plays he wrote. But it omits (at least) one — Kisa Gotami, published in the Berkeley Bussei in 1957.

The story of Kisa Gotami can be found in the Buddhist canon. In sum, it’s the story of a mother whose child dies. Overcome with grief, she wanders, crazed, carrying the dead child in her arms. She seeks out the Buddha who, she learns, has miraculous powers. She begs him to bring her child back from the dead. And he agrees, telling her that first she will need to find mustard seed from a home in her village that has not experienced death. Of course, she can’t. Every house she goes to has a story of a child, parent, grandparent, aunt, sibling who has died. And with that she realizes the universal truth of death. (And, in good Buddhist-sutra fashion, she renounces the home-life and joins the sangha.)

Kashiwagi’s dramatization of this story is moving and unsettling.

It opens with a woman who is overcome with grief. Her husband is at turns compassionate and violent. She wanders into the forest and encounters Kisa Gotami, described as a “shabbily dressed woman of indeterminate age.” Kisa Gotami approaches the grieving woman and tells her of her own experience with grief. The loss of her baby, the desperate search for a cure, and her encounter with the Tathagata, the Buddha, who asked her to search for the mustard seed. The drama is accompanied by a chorus who describe the scene and set the mood and add a mournful backdrop to the meeting of these two women, these two grieving mothers. At the end of Kisa Gotami’s story, she is able to let go her child, and the grieving woman, also released from her grief, returns to her husband and family.

I must admit that this story is particularly difficult for me in my present state of mind, coming to terms with my own grief. I can’t help but feel as though this is a terrible story. In the midst of grief, to be told that “everyone dies” is not particularly helpful. I recognize that the audience for the original story was not, of course, me but rather a monastic sangha who had committed to the life of a renunciant and perhaps needed some encouragement to remain committed. It is not a pastoral story (as my mentor Richard Payne would say). Moreover, I imagine Kashiwagi’s dramatization would be unsettling with its grieving mothers backed by a mournful chorus. But, of course, its unsettling power is derived from the simple fact that — it’s true.

Leaving aside my personal experience of reading the play, and returning to my role of historian, I know that this play was not just printed in the Bussei but also performed at the Berkeley Buddhist Temple. In her memoir, Kaiyko, Jane Imamura (the wife of the resident minister, Kanmo Imamura) mentions this play and includes a photo of the performance.

Perhaps the most immediate thing you notice in this photo is the male lead, George Takei. Takei and his family were incarcerated during World War II like Kashiwagi, and afterwards he finished high school in Los Angeles before studying architecture at UC Berkeley. Imamura doesn’t mention much about the performance of Kisa Gotami in her memoir other than this photo. If the script was published in the 1957 Bussei, the play would have been performed around the same time. I’ve heard stories (which I cannot locate at the moment) that Kashiwagi was so impressed by Takei’s performance that he encouraged him to pursue an acting career. Takei transferred to UCLA at some point in the late 1950s and completed his degree, and then a master’s, in theater. And then, well, you know — went on to captain the USS Excelsior.

I am convinced there’s more to this story than I’ve told here, more than any one person knows for sure. I have only given the barest of facts which, in themselves, are remarkable. There are currents running through American Jōdo Shinshū communities that connect the tradition in unexpected ways to more familiar American pop-culture icons. Takei’s Buddhism is not a secret of course (he was married at a Buddhist temple after all), and legitimating Takei’s Buddhist bona fides is not my concern. I am more interested in speculation. I am more interested in asking what if?

Let’s assume for the moment that it’s true, that Takei became an actor only or primarily because of his experience at the Berkeley Buddhist Temple and Kashiwagi’s encouragement. Then let us ask, what if? What if that had never happened? How would the world be different? Surely, Gene Roddenberry would have cast some other actor as Hikaru Sulu. But then we’d live in a world with a different Sulu, like some alternate reality where Tom Selleck was cast as Indiana Jones.

This may seem trivial. But I contend (it’s a hill I’m willing to die on) that it’s the sum total of trivial things that makes the world what it is. And in the case of Star Trek (and American Buddhism), we have Hiroshi Kashiwagi to thank for the world as it is.

Leave a Reply